Bill Martino

For whatever it might be worth, I try to bury the bad and the sad and recall only the glad and this is advice I will offer to all and urge them to take. This post may have nothing to do with khukuris or Gorkhas but it is a "glad" recall that I want to share:

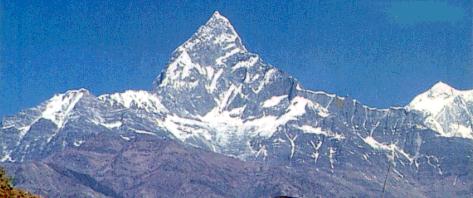

Sunrise in Pokhara.

Pokhara is Nepal's second largest city but you could not tell by looking. It looks more like an overgrown village. There is a lake there, Phewa Lake, and the Himalayas are nearby. It is a beautiful place. Yangdu and I went there years ago when we were getting to know one another -- I was too old and she was too young but an automobile accident later that nearly cost her life made us change the way we viewed age and made us realize there were no guarantees and that, in reality, age was a number and nothing more. Take what God and your karma has offered and make the most of it.

We stayed at a small hotel called the Tragopan, near the lake. Our first morning I arose early, letting Yangdu sleep, and went to the roof of the hotel to await the sun. A hotel boy had made me a pot of coffee and I had my Gaida (hippo) cigarettes so I sat alone sipping coffee and smoking, in absolute silence and darkness, waiting for the sun. The first gray light of false dawn came and I could make out the awesome silhouette of the Himal to the North. Then the snow capped peak of Mt. Pucchare (26,000 foot + fishtail mountain -- virgin peak of the Himalayas, no climbing permits issued for this one) began to take form, turning pink at the top and slowly growing from top to bottom, pinks and snow whites.

There is no way to describe it -- all the words fail -- awesome, beautiful,

inspiring, breathtaking, magical, -- it was all of these and more. More sun

and more peaks, Dhaulagiri, the Annapurnas, like an omniscient artist painting

a picture of almost unbearable beauty. I was swept up in the beauty, the

closeness, I felt like I could actually reach out and touch what I was viewing

and a great peace enveloped me. I knew that this experience was going to

be with me forever and I suddenly became thankful for all the great blessings

that had been given me -- I could see the beauty, I could hear the beauty

of the silence, I was One with the Universe and felt like I was perhaps the

most fortunate man in the world.

Bill Martino

The Story of Ali

I first met Ali Tamang years ago when I was living at the

Tushita Rest House in Kathmandu. The place had once served

as the US Embassy in Nepal but as usual the US personnel had

moved on to bigger and better things. It was a modest

establishment that catered to budget travellers, mostly

climbers, trekkers and upscale volunteer workers. I was the only

American residing there and one of the few permanent guests.

The first time I saw Ali he looked little different from any of the

myriad of street urchins one runs across in Kathmandu and all of

Nepal for that matter. 10 or 11 years old, dressed in rags,

barefoot, lice in the thick black hair -- and tearful. He was

mopping the cement floor of the dining area. My usual waiter,

Govinda, brought my coffee and I asked him about the new

boy.

"Sad case," Govinda said. "His name is Ali Tamang. His parents

died just recently leaving him and his 14 year old sister alone on

the farm. Of course, two children cannot run a farm so they

came to Kathmandu to try to find work. He's young and knows

nothing of hotel work but the manager took him on out of pity."

A common story in Nepal. Ali was at the bottom of the pecking

order in the hotel and most of the other boys tormented him

and gave him all the worst possible work -- cleaning the

charpis, mopping, all the dirty work. Of course, it broke my

heart as did most of what I saw in Nepal.

One morning when I was having my coffee I called Ali over to

my table and spoke with him. He told me his story and was very

concerned about his well being and future -- if any. A hotel boy

barked at him to get back to work. I told the boy he was at my

table by my own invitation and to leave him alone. The boy was

wise enough to do nothing but nod and smile. I was one of the

few who left "boxies" -- tips -- and as such was a preferred

customer. If one is wise one does not bite the hand that feeds.

Upon leaving I stuffed a 20 rupia note into Ali's hand. "For me?"

he said, astounded. "For you and you alone," I said. Maybe 50

or 75 cents at the time but perhaps a week's pay for Ali.

Next AM when I had my coffee I asked that Ali be my waiter.

The other boys balked, saying he was not a waiter at all but a

common "chami" (cleaning man or janitor -- often the caste to

which I was assigned by the Brahmins). I called the manager,

Prem, over and put my request to him. The "don't bite the hand

that feeds" wisdom came into play again. I was probably the

only permanent guest in the hotel. I took many meals at the

restaurant and LEFT BOXIES. I drank beer and khukuri rum in

the evening with a group of Nepali friends and LEFT BOXIES.

Sometimes I would bring guests from the Peace Corps and buy

them drinks and dinner and LEFT BOXIES. "If you want this boy

for your waiter you may certainly have him, however, it is my

duty to warn you that he has no experience as a waiter so if

your service is poor you have no one to blame but yourself." I

said, "bringing a pot of coffee requires little skill. I'll take my

chances."

And so Ali became my coffee server for the mornings and was

able to earn the coveted boxies left by the crazy queerie. Ali

got rid of the lice and was able to buy come chopples so he

didn't have to go barefoot and got a better shirt and pants. He

still slept on the bare concrete floor at night with no blanket or

pillow. Not an easy life being an orphan hotel boy.

Fall drifted into winter and Christmas was soon upon on us.

Some creative fellow on the hotel staff made a cardboard

profile of Santa and painted it red and white and set it in the

restaurant. A red and blue light bulb decorated the Santa. Not

much, but something, and enough to bring the Spirit of

Christmas upon me.

A couple of days before Christmas I spoke to Prem. "I want to

use Ali for 3 or 4 hours today. I need some help at the market."

"Of course, Bill Sahib. No problem."

So Ali and I went to the open market in Assan Bazaar. I bought

him some jeans and shirts, sports shoes, socks, a good warm

jacket, blanket and pillow. At first he didn't understand what I

was doing but when it finally dawned on him these items were

for him I've never seen a happier boy. When you have nothing it

is strange just how much joy a couple of simple gifts can

generate. Bottom line, Ali went back to the Tushita looking like

a jewel with a smile that was worth a thousand times more than

the few dollars I'd spent.

Back at the hotel I had a little talk with Ali. I said, "Son, nothing

in this life is free and neither are these clothes I bought you

today. I expect you to repay me. From this day on I want you

to deliver my morning coffee to my room. At 7Am I want to hear

you knock on the door and I want that coffee to be hot and

strong as you know I like it."

"I'll be there every morning" Ali said -- and so he was and with

that great smile.

When Yangdu and I got married I took Ali from the Tushita and

he became our "house boy." It was his duty to clean the house,

do the shopping, run errands and be general handyman and

gofer. He became like our own son and we loved him and he

loved us.

I had to leave Nepal and return to the US and make

arrangements for Yangdu to join me. A life in Nepal seemed

impossible for us. I could not tolerate the government

corruption which required a song and dance I refused to do in

order to stay and gain employment in the country. Ali and

Yangdu stayed together and waited. Finally, I got all the papers

together and Yangdu joined me in San Diego. Ali went to work

for Yangdu's sister, Sanu. He lasted a year or two and

disappeared but it was not to be the end of Ali.

Years later Yangdu and I returned to Nepal to visit. For some

reason I walked into a trekking shop in Thamel. A young man in

the group of Nepali trekking leaders waiting for cutomers jumped

up, ran over and hugged me. "Bill, Sahib! It's me, Ali!"

The ragged lice ridden boy had turned into a tall, very

handsome young man, well dressed, polite and still with that

broad overpowering smile. He turned to the other men in the

shop and said, "Boys, I want to tell you this man is like a father

to me. When I was a poor hotel boy he took me in and treated

me as his own. I will never forget what he did and will always

remember him -- And, now he has returned to see me again."

We had a wonderful reunion and Ali told us of what he had

done. He had learned a smattering of English when he was with

me and had listened to advice I had given him. He had gone to

school part time and had perfected his English. He changed his

name to better fit a trekker's image, and had got on in a

trekking shop as a kitchen boy. He worked hard and learned the

routes and as much as he could about trekking. This along with

his English language ability soon got him promoted to a trekking

guide. He studied and learned Japanese so he could take

Japanese trekkers on journeys through the Himalayas and had

become a top guide -- well paid and respected in trekking

community. He had overcome great adversity and had become

by any standard a success.

And therein lies the reward and what a great reward it is. Many

thanks, Little One, for making my life so much better.

I forgot one thing: What has this to do with khukuris?

Bill Martino 3/01

Pix of Yangdu and Ali at Bill's old deera in Swayambu.

On King's Way in Kathmandu, the biggest and finest Boulevard in all of Nepal, where the rich tourists stay at the five star Yak and Yeti and Annapurna Hotels, up maybe fifty yards from the Annapurna is a section of sidewalk where beggars sit in the hot sun of summer and dark, cold days of winter hoping for a few paisa to keep them from starving.

You will see in this group some blind, crippled, deformed, sick and a few Sherpas who have lost hands and feet to frostbite. Most tourists and rich Nepalis passing by ignore this unpleasant sight, a few will toss a ten rupai note into a cup and then quickly move on.

When I passed by I would try to give a few rupia to what I judged to be the worst off of the bunch. I had learned quickly that I could not support every beggar in Nepal and would have to be selective no matter how difficult that might be. I always gave something to the Sherpas.

Since I passed this way almost daily I started to get to know some of these beggars and there was one who quickly became my favorite. His name was Raj which means "king." He had some sort of birth defect which left him paralyzed and deformed from waste down. I suspect he was maybe 4 foot six and weighed maybe 80 pounds. His parents would roll him out to his space on the beggars showcase on the sidewalk each morning on a cart made of wood which rolled on metal wheels. And, he would sit there all day hoping for enough paisa to make his service worthwhile. Then his parents would come pick him up at dusk with his Nepali style wheelchair and take him home.

What attracted me to Raj was his attitude. Unlike most beggars who will hold up their cup and show tears in their eyes, Raj always smiled brightly and gave me a hearty "Namaste" when I passed by. He always asked about my well being and tried to chat. He never really begged or held out his cup. Amazing to me, he seemed happy, and caused me to wonder how this could be. I soon found myself lingering there with the beggars and chatting a few moments with Raj. He was a bright and a very positive fellow for a man in his circumstances.

As time passed Raj and I became friends and I would sometimes sit on the sidewalk with him and spend an hour or two just talking. Seeing me there, a Westerner, seemed to be of great concern to the tourists who walked by and I must admit even my Nepali friends thought it not a good idea to sit with the beggars. Hardheaded SOB that I am I paid no attention to any of this and simply continued my relationship with Raj.

I was in Nepal trying to learn about life, death, Buddhism, and myself. Raj was to become one of my gurus. He taught me that regardless of the cards one might be dealt in this life one can make the best of his hand. Raj was a beggar who did not beg. He was a man of honor and principle in a loincloth. He was cheerful and looked for the best even though he lived in a deformed and near helpless body and survived because of the generosity of others. He showed me that what one sees and what really is can be at the different ends of the rainbow. He became not only a teacher but an inspiration to me and what I learned from him alone made all my efforts seem worthwhile.

As always is the case, Raj gave more to me than I ever gave to him, and he showed me who the real beggar was.

When I left Nepal the last time I went to Raj and told him I was leaving and asked for his blessing. He blessed me (it is very valuable in karmic terms to receive the blessing of a beggar) and we both cried upon parting.

Raj, king of beggars, I will never forget you and I am just as certain

that you will never forget me. And, Raj, wherever you may be I send you my

eternal gratitude for all that you gave to me and did for me.

Bill Martino

In the Kathmandu Valley many homes have a roof of poured cement. It is strong,

generally leakproof, makes a solid floor if additional stories are to be

added, and it provides space that a gabled roof does not provide.

Consequently you will see a lot of activity on the rooftops in Kathmandu and surrounds. Some people raise small crops and house a few chickens on the roof. Laundry is generally done on the roof and clothes draped down the side of the wall to dry in the sun. The colorful saris wafting in the breeze are a beautiful and unforgettable sight. Meals are sometimes eaten on the roof.

When Yangdu and I had our apartment in Swayambu just a ten minute walk down the hill from the temple I would often write on the roof. It was warm and sunny and I could see the glowing golden spires of Swayambunath up on the hill in the setting sun and hear the bells and tsankas (sp -- the big long horns the Buddhist monks play). Very conducive to creative writing.

A couple of houses over from us lived a Tamang man. What work he did I never knew but he would leave early in the morning and return home an hour or two before dusk in the evening. It was his ritual upon returning home from work to go up on his roof, play his flute which is called a "basari" in Nepali and sip from a half pint bottle of Khukuri rum.

The music he made was magical -- haunting -- sometimes sad, sometimes lively and happy. When he played I generally stopped writing and would simply sit and listen. I am sure he was a laborer of some type because of the clothes he wore to work but I felt that he should have been a professional musician. He did things with that little bamboo flute that I could never do and I admired and appreciated his talent.

Sometimes he would look at me while he played and he knew I was listening and watching him. Sometimes he would wave and I would wave back. We became friends of sorts but never met -- an unusual but nonetheless valuable relationship. If for some reason he missed an evening I felt empty, like something was not complete. If I was downstairs in the apartment and heard him start to play I would go up on the roof to listen and he would stop for a moment, wave and smile. I think he appreciated me as his audience.

Strange, perhaps, that we never met and that I do not know his name but I remember him vividly -- the Tamang on the rooftop -- and there are times when I think about the wonderful music he made for all of us and I now wish I had taken the time to go meet him and thank him. I doubt that now we will ever meet but I can still thank him. It is never too late for thanks.

So, thank you, Tamang on the rooftop, for all those wonderful songs you played. I can still hear them sometimes in the dark of the night when I lay awake and remember that wonderful and magical life I lived in Nepal.

Heard melodies are sweet but those unheard are sweeter.

Dhanyabad, bai!

Bill Martino - 11/99

On one of my return journeys from Nepal I was carrying four bottles of Khukuri rum just like the one is this picture. At Narita I was passing through security. Everything was going just fine but then the gal doing the x-ray of my carry on got big eyed, gave me a quick once over, picked up the phone and made a call. In maybe ten seconds four airport security guards were upon me.

"What do you have in your bag?" one of the guards asked.

I was surprised because although polite and courteous, the guards seemed tense, nervous and much too serious. Posture said a lot, too.

"The usual stuff," I replied. "Socks, shorts, a few clothes, shaving kit and some rum."

"You have some weapons," the guard said. "Some very large knives."

"No, I don't. I have a pair of little scissors and some nail clippers."

"Would you please open your bag?"

"Sure," and I did.

When the guards saw the bottles of khukuri rum they all broke up, laughing and slapping their legs. They had been set for possible trouble and got a few bottles of rum instead. Then with the customary Japanese politeness they apologized.

"We are so sorry to trouble you but the x-ray machine showed these bottles as weapons. We thought you had four big knives you were trying to take aboard the plane. So, sorry."

So, that was the end of it and the dangerous old desperado, Uncle Bill, boarded the plane with the khukuri rum and flew away to the US. BM

(Khukri XXX Rum is produced by Nepal Distilleries Pvt. Ltd.

in Nepal. HW)

As most of you already know at Himalayan Imports we march to a different

drummer and this is true with our pricing policy. Let me start with another

of my many Nepal stories to help you better understand.

In 1988 Yangdu and I spent two or three months in Nepal, visiting, going

to our favorite temples, and laying groundwork for what was to become Himalayan

Imports -- which should have been "exports." During that period I hired a

young Brahmin man named Govinda to do some work for us. When he had completed

his assignment I asked him how much pay he wanted for his work. He told me

the amount in rupia which converted to about $35 USD. I said that was not

enough for what he had done and handed him a hundred dollar bill. He started

to cry, dropped to his knees and tried to kiss my feet! Remember, this was

a Brahmin and I am an untouchable. I scolded him and told him to get up that

it was only money. He looked up to me and said, "It may be only money to

you but to me it means medicine for my sick daughter!" This is the story

of Nepal and it is a sad and desperate one.

I have seen children some as young as six toiling in cement and brick factories, their little bodies white with dust, only the eyes not dusty white, peering sadly out of the ghostlike forms. I have seen boys ten years old working in hotels 15 hours a day, seven days a week, cleaning, mopping, washing dishes, sleeping on the cement floor at night and happy to receive a couple of plates of dalbhat and a cup of tea per day and maybe five dollars per month. This is also true of the more commercial "aruns", blacksmith shops. You will see a poor child gathering charcoal, pumping the handle on the forge, sitting on the dirt floor filing and sanding a blade, perhaps even trying to hammer some hot steel for a master kami who himself may be too old to work but does anyway because it is either that or starve.

The last order I placed with old Kancha Kami was for six pieces of his Sherpa style which we had nicknamed the Kancha special. The price he asked amounted to about fifteen bucks per knife. I told him that I wanted him to take his time and do an especially good job for which I would pay considerably more per knife. Kancha was very poor and sometimes had nothing, not even a potato in the house to eat. He was most grateful.

Because of these deplorable conditions in Nepal, I know that I pay more than is necessary for our khukuris, try to employ errand boys, people to wrap and pack, and do odd jobs that are primarily "make work" efforts and I charge accordingly. I could get the khukuris for less, (much, much less if I were to use one of the major shops in India or Pakistan who have the capability to make our khukuris to our exact specifications and have offered to do so, telling us that we could claim the khukuris were made in Nepal and nobody would be the wiser -- except me!) reduce my price, sell more and make more because of volume but I choose not to do this because I like to be able to look at myself in the mirror when I shave. If I were to beat the kamis down to bottom dollar, toss out the little guys who help in between the shop and here, I would be contributing to the exploitation of some of the poorest and most desperate people in the world and I simply refuse to be a part of that. Bill Martino 3/99

One of my most memorable moments was in front of the great temple at Bodh

Gaya. I had brought a large sack of fruit from the market for the beggars.

As I handed it out a large crowd of stretching hands materialized in front

of me. I gave the last piece to an old woman, and as I did, I met the eyes

of a beautiful young beggar woman. I had nothing left to give her. We looked

into each other’s eyes for a moment, and there was a mutual understanding.

I still remember her eyes.

It is true that there is suffering, and sickness and death in Asia. When

I traveled there as a young man my traveling companion returned to the US

after a couple of weeks. He was not prepared to see hungry children and untreated

wounds.

It is easy to imagine the Buddha coming out of his father’s palace in Nepal, and discovering sickness, suffering, and death in the surrounding countryside. The realities that caused him to discover his four noble truths are still there. But they are here in wealthy America also.

There is great wealth in Nepal. Many smiling faces. It is not necessarily a benefit to export our lifestyle without an intimate understanding of its impact. Bill has understanding, respect and love for the people of Nepal. This is what makes his compassion real and effective.

The kamis are performing an honorable service to the world, by using the methods of their fathers to produce blades of the highest quality. They are able to put their heart and spirit into the work. It shows. The blades they are sending to this country are of great value.

Perhaps it is the untouchable blacksmiths who are demonstrating their compassion

for us? HW 3/99

Copyright (c) 1999-2001 by Howard Wallace / 2002-2003

by Himalayan Imports,

all rights reserved. maintained by Benjamin Slade.

This FAQ may not be included in commercial collections or

compilations, or distributed for financial gain, without express written permission

from the author. This FAQ may be printed and distributed for personal

non-commercial, non-profit usage, or as class material, as long as there

is no charge, except to cover materials, and as long as this copyright notice

is included.